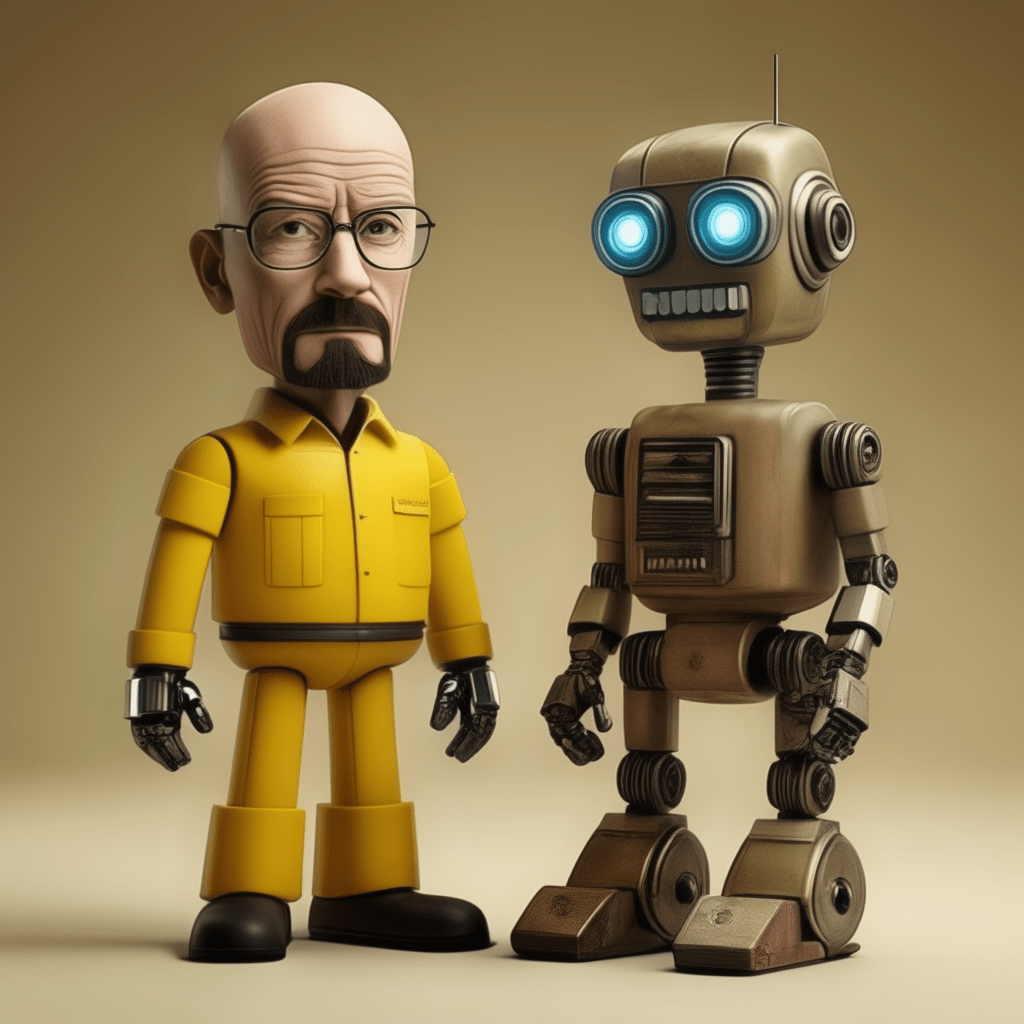

This specific solution that I am going to discuss came to my mind while binge-watching Breaking Bad. In one of the episodes, Walter White is out shopping in a home improvement store when he sees a guy loading his cart with products, which individually otherwise are primarily used for different purposes. But together, these can (or are) used to cook meth. He advises the guy that he should split his purchase and buy them from multiple stores, to avoid suspicion.

Of course, it is Walter’s “expert knowledge” that allows him to identify that those specific sets of products, purchased together, can be used to cook meth.

The good news is, we can teach an algorithm to identify such patterns as well!

The central theme of the movie “Minority Report” was the ability to predict if a crime is going to happen and arrest the person beforehand. Technically and legally, that is still far far away from reality (but then I don’t know what kind of data Musk’s neural implants are already collecting). While that exact scenario is certainly not going to be a possibility, we are certainly in an age where AI algorithms are leveraged to proactively avoid bad things from happening, like critical machine failures on shop floors, or blocking a fraudulent credit card transaction.

But can AI help proactively prevent some other types of crimes from happening?

Digital forensics is already leveraged, after the fact, to build a case against the defendant in many cases, including white-collar crimes. However, there is an opportunity to leverage AI algorithms to prevent potential crimes from happening.

Many types of crimes, before they happen, need some input to be executed. If the executed crime is an end product, you need raw material, including the human mind. While the ability to peek inside the human mind may be out of reach, we can control some other inputs from getting into the wrong hands. And we do that already.

There are many types of chemicals and substances that you can’t easily buy unless you provide explicit documentation that you need them for specific legal purposes. However, there are plenty that can be bought easily separately, and together, they can be used in many ways, some of which are against the law.

The suspicion element during the checkout, as suggested by Walter White, in the opening paragraph, comes into the picture only when a cashier is familiar with the process of cooking meth, and hence the ingredients involved in the process. So chances are slim to none. But here is where AI algorithms can come into play. In fact, they can not only stop someone from making that purchase, but they can also do some descriptive analytics to understand if the person has made that kind of purchases before. This is just one example, but the fact is that such an algorithm can perform a variety of descriptive and predictive analysis to prevent unscrupulous purchases in stores.

You would argue that supermarket chains would not benefit commercially much from this. And this is where the good part comes into play: They do not need to develop an algorithm exclusively.

To understand where I am coming from, let us explore the concept of an “on-the-floor” kiosk that can help you with a list of items you may need to complete your project.

The underlying concept behind such a kiosk is simple. Like the game of 20 questions, a kiosk at a home improvement store can dole out a list of products that are needed to complete the project, and the aisle they are in. In fact, a vanilla version of this has already been implemented on websites of leading home improvement chains. The algorithm can be further refined, to make it more interactive and “on-the floor”.

This algorithm can then become a foundational algorithm, the variations of which can be leveraged for many different purposes. The commercial applications go beyond the real-time on the floor recommendation. You have to remember that the data that is needed to train these algorithms, and the learning aspect of a deep learning algorithm, can be repurposed for many different variations, with minimal additional training. An example is market basket analysis. The fact is, once the challenging part of data foundation and initial training has been completed, there are so many ways you can repurpose this capability.

One of them is this non-commercial use suggested in this article, which can benefit the communities in which these stores operate. The social impact and goodwill can be enormous, and the effort is so little since the algorithm will recoup ten times the investment from commercial applications in a year (if done right). The menace of narcotics that are cooked in shady labs, with raw materials procured from stores, can be significantly controlled in areas that are hard hit, leveraging this approach. What may be needed in some case though is some local legislation to take care of some legal aspects of this sort of purchase profiling though.