“There is no certainty…only opportunity.” – V (From the movie ” V for Vendetta”)

While many in North America, specifically in United States, may not be familiar with the game of cricket, almost 2 billion people around the world consider it their primary sport. As they say in the Indian subcontinent, cricket is followed almost like a religion. And all the key cricket playing nations currently are competing for the ICC Cricket World Cup, held every four years. Being a cricket fan, and due to the fact that I have time to kill, I am following almost all the matches (games) of the tournament.

The game of cricket has few elements common with baseball. Both games share common terms such as innings, umpires, runs and outs.In fact, some baseball historians believe that cricket is the ancestor of baseball. There is definitely a link but in my opinion, not a parent-child link.

Both cricket and baseball are bat and ball games. They both have the concept of batsman and bowlers, with a different nomenclature of batters and pitchers in baseball. Bowlers or pitchers throw the ball to the batsman or batter and the batsman or batter hits the ball. Players in the field try to catch the ball. Both games use two umpires.

Batters in both these games run between or around markers or milestones to score runs or points, whereas the fielding team tries to get the ball to those things (wickets in cricket or bases in baseball), or fielders near them to stop those runs.

Batters can hit the ball out of the field to score runs (six or four runs or a home run). Teams change roles after a set of batters are out. Finally, after opportunities for both teams to bat, the team with more runs wins.

One of the many ways a batsman or batter can be declared out in the game of cricket, is leg before wicket. As the Wiki definition goes:

“Leg before wicket (lbw) is one of the ways in which a batsman (now officially termed a ‘batter’ since September 2021) can be dismissed in the sport of cricket. Following an appeal by the fielding side, the umpire may rule a batsman out lbw if the ball would have struck the wicket but was instead intercepted by any part of the batsman’s body (except the hand holding the bat). The umpire’s decision will depend on a number of criteria, including where the ball pitched, whether the ball hit in line with the wickets, the ball’s expected future trajectory after hitting the batsman, and whether the batsman was attempting to hit the ball.”

As you can imagine, there is a set of criteria that an umpire needs to take into account to make a lbw decision. And since the criteria is subject to interpretation, law decisions in the past had been the genesis of many controversial decisions. Then came technology.

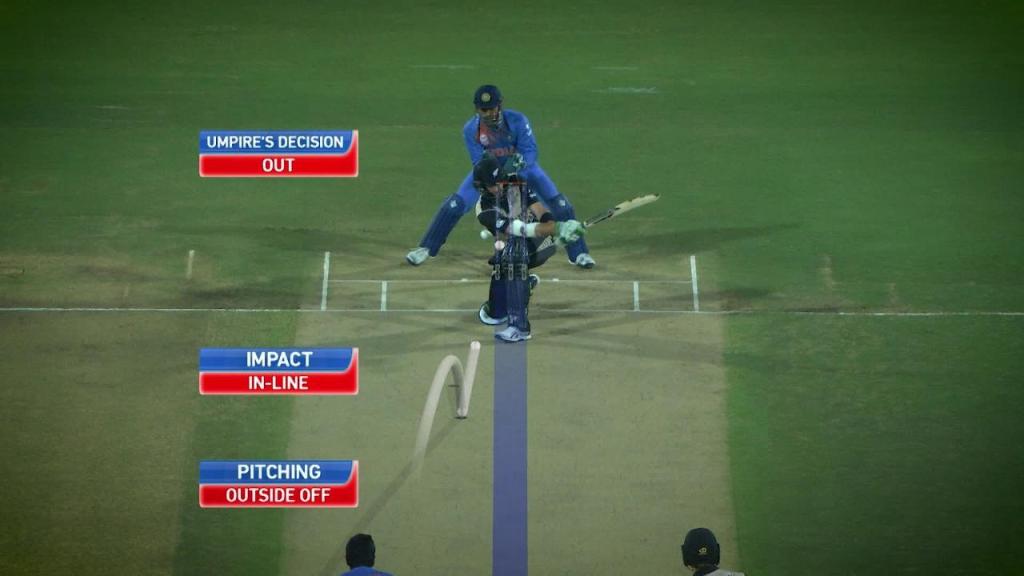

Algorithms now can help map the course the ball “could have taken”, a form of predictive analytics. This ensures transparency, where a batter can challenge an umpire’s decision and request a review by what is known as a Decision Review System (DRS) . The screen grab below shows how prediction of the path of the ball by DRS looks like.

As I follow the games of the current tournament, I notice that many DRS reviews are inconclusive, and for such instances, the onus eventually goes back to the umpire to make the final decision. Whether the players like it or not. And in my mind, this beautifully captures the reality of the AI algorithms maturity today and can be used as an example to set expectations.

The algorithm’s technicalities are not public but are not difficult to estimate. Pace, bounce distance, trajectory pattern, angular deviation, wind velocity, and direction are examples of attributes that can be factored into the algorithm.

But what is important here is that the algorithm is not always certain. In our struggle to justify AI as the panacea for everything, we sometimes ignore the fundamental concept of confidence intervals. Confidence intervals exist because there is a level of uncertainty embedded in everything around us. Cricket or business operations, as quoted in the beginning, “There is no certainty…only opportunity.”

Coming back to the DRS system, when the system indicates that there is a “close call”, i.e, it is not confident enough to make a call, the decision goes back to the human in the loop-the umpire. And this is how we need to think about designing AI algorithms for business planning.

Due to the intense level of gaslighting, we are made to believe that AI has the capability to take over intricate tasks that humans perform to the point where it can even exterminate humans. Fortunately or unfortunately, that is not true in the current state. And there are reasons why it will also not be a reality in the near term. But the crux is that humans will be, or need to be, involved in instances where complex decision-making is needed.

Business planning methodologies are typically divided into strategic, operational, and tactical buckets. If you peel the onion layers, you will realize that as you move from strategic to tactical, the decision-making becomes more quantitative. For example, while you need to consider the evolution of the economy, market, and consumer behavior for the strategic decision to expand/consolidate your distribution network, planning your day-to-day operations becomes more numbers-driven.

But the fact is that even if you leverage AI for all these levels, you will need umpires across all levels of planning.

I believe it is possible to build an intelligent DC algorithm to help you plan optimal daily warehouse operations in real time. But even that capability will need human governance. Umpires will need to make the call now and then. And why is it important for data science professionals to understand?

The reason why we must understand the fact that “There is no certainty…only opportunity.” is because we need to design algorithms accordingly. Sometimes, we start chasing the impossible with algorithms. Gaslighting around us adds to the perception that AI algorithms can accurately and precisely do insane tasks. But suppose we accept the fact that in many circumstances, they can not, and a human will get involved. In that case, we will waste less time designing perfect algorithms (unsuccessfully, even though we don’t like accepting that). We can instead focus on optimizing the human-AI approach to designing solutions (rest assured, we can work together, and AI will not exterminate us).

We will discuss more in this week’s episode of “Think About It”.