My thoughts on this topic originated when reading about the UWA strike. I will not get into the validity of the grievances that workers have. That is a different topic and one that I best left to experts. I am not an auto industry expert, and neither do I follow the market that closely. So, the gist is I am not qualified to take sides.

However, pondering about these manufacturing workers diverted my thoughts in a different direction. I ended up thinking about the impact of manufacturing automation on human workers, and then my thoughts drifted into the automated manufacturing lines that most large automakers tout and flaunt.

The connecting link for me was that since most of the manual tasks are handled by robots, the workers left on the floors must have a skill set higher than their previous generations. If that is the case, the increased skills requirement should be reflected in salaries. If that is not the case, maybe we still have not optimized how we automate manufacturing and warehousing?

But keeping that debate aside, we know that every investment in automation comes with increased productivity. That is how business cases are made. But what exactly defines productivity for defining these business cases? Are you producing more with the same resources? Producing more with fewer resources?

This two-part article overviews a high-level framework to start thinking about the automation strategy. You can find the first part here.

Every investment in automation comes with an increase in productivity. But what exactly defines productivity? Are you producing more with the same resources? Producing more with fewer resources? Any way you measure productivity, a robotics implementation can be proven productive by producing more. And this is what most organizations end up doing in make-to-stock situations. Inventory may increase, but that inventory can be tactfully dispersed in the system. It will not get noticed till much later.

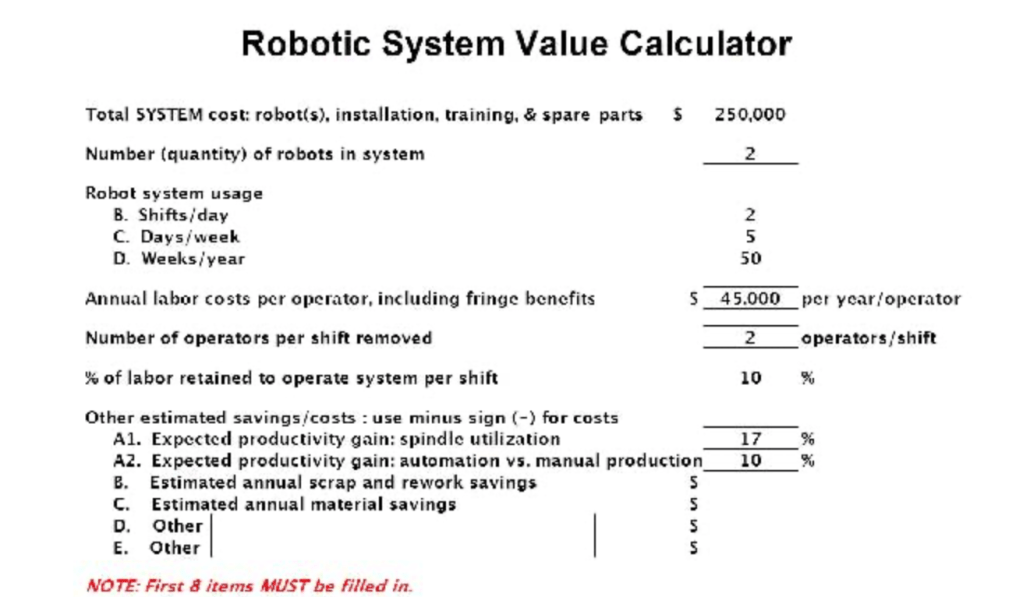

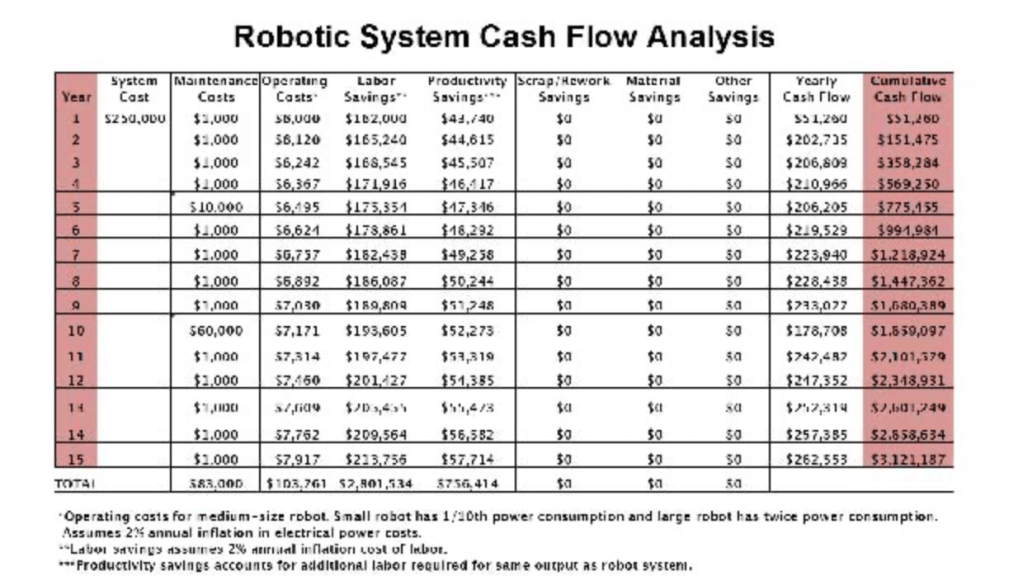

For example, let us review the template from the website automate.org. You can pick any business case methodology for automation and find the same central theme of productivity improvement. But let us try to understand why it may backfire.

It is a no-brainer that you can produce more with bots. But a couple of key questions are:

- Do I need to produce more?

- Is over production due to productivity improvement optimal for the business overall?

Let us try to understand this with a simplified example. ACME’s factory A produced 5000 parts of SKU B monthly before automation. Post automation, they can now produce 6000 due to increased efficiency. This is the amount they have to produce, to keep the bots productive and utilized.

The reason automation investment was made in factory A was because there was increased demand. However, the automation strategy did not match the plan optimally. Once the bots were in place, their utilization also became imperative. The ROI calculations assumed that the 6000 units that will be manufactured will all be sold.

A year later, that does turn out to be the case. 6000 units sell but not at the standard price. Inventory goes up, leading to markdowns. There are associated inventory holding costs to hold the additional inventory, and markdown and obsolescence costs, that were not accounted for in the ROI calculations.

To illustrate this further, let us use a couple of elements from the four elements highlighted in the first part of this article. This will help highlight why robotics investment is much more complicated than the worksheet above.

Process Transformation and standardization:

Automation can lead to overproduction if you do not redesign your manufacturing processes to sync with demand (even with a lag). More so in mass production. You lose your flexibility from having a human workforce to some extent.

Also, the most crucial aspect that many manufacturing organizations ignore is syncing robotics strategy and manufacturing processes. While some industries may find robotics that fits their manufacturing processes precisely, that is not always the case. If you force fit bots in your manufacturing processes without making process changes, you end up with “illusionary” productivity gains, or worse, gradually decreasing productivity. Build simulation models to evaluate the process for a long duration instead of relying on estimates from those selling the robots.

This applies more so in warehousing robotics. Various options are now available, and I often see a completely wrong type of bot being leveraged. Unlike manufacturing, warehouses have more flexibility with robotics installation. Hence, evaluating the alignment of warehousing SKUs, slotting, processes, etc., with the type of bots is critical. For example, a specific category of bots is totally unsuitable for CPG that I often see used in retail chain warehouses. They may not have done the precise analysis (or did not want to), but they may have compromised productivity or been stocking higher than the required volume to justify the infrastructure.

The approach with manufacturing and warehouse bots is precisely the same as our approach with “AI.” We invest in a solution without doing the strategic presswork, hoping that the technology will help us transform. The fact is, it is always the people and processes. Technology, after all, is just an enabler.